The Future Of Restaurants

1. The King of Chaos

Chef Diego Argoti in his natural state.

It is 2024.

We arrive at Rich Table without a reservation, but I didn’t think to make one. Chris and I are with good company, you see: there’s Sincere of Tacos Sincero, a lauded Chino-Latino pop-up that serves kimchi carrot tostadas and twelve-hour brisket with labne; Andy from Sushi Simpin, who brings his experience from Nobu to sling Michelin-level sushi from his small apartment in San Jose, sometimes while wearing leather fetish gear; and, of course, Diego.

Growing up in Burbank a stone’s throw away from Disney and Warner Brothers, Diego’s love of cooking was perhaps kindled by his father, who managed several grocery stores in the San Fernando Valley. He would bring home food that he had to get rid of but was still good to eat – whole lobsters and rib eye steak prepared with love for his family as soon as he could get home, sometimes at 1 am. Sometimes waking Diego up to eat.

The first dish Diego learned how to make in culinary school was Fettuccine Alfredo. He started cooking in kitchens when he was still a teen and soon made his way into some of LA’s best restaurants. He drank, took drugs, had sex, and did a brief stint in Philly, but that didn’t let him get in the way of his dreams. It is 2018. His work at Bestia led him to a sous-chef position at Bavel, which he helped open and soon became LA’s hottest res. Some of its recipes were his recipes. He drank even more. Yelled a lot. Everything was in its right place.

Then, the Pandemic happened (it is, of course, 2020). For the first time since he could remember, Diego could not turn to work to quell his restlessness. He dug inward. Became Cali-sober. And one day, some ideas came to him: buffalo frog legs, cheeseburger ravioli, tortellini al brodo but the broth is pozole, Spam and eggs but the Spam is beef tongue, Froot Loop ice cream not made with actual Froot Loops, vegan dan dan noodles with pickled mushrooms and blueberries. Estrano exploded into LA’s pop-up scene with cooking the likes of which no one had ever seen. Popping up in parking lots of established restaurants, blasting cumbia, and charging what fellow Industry-folk could actually afford, Diego also had something to say. He did his best to stop yelling and really stuck to it. He accepted substitutions (not that anyone wanted them). And he passed out shroom gummies to his patrons waiting in three-hour long lines, he gave diners an experience for which they had no framework.

Via @estranothings

Via @estranothings

Recognition followed in due time – a consulting job here, a blue-checked Insta post about him there. In 2022, he was approached by Button Mash, an Echo Park arcade bar once known for its potstickers, to revamp its food menu via an executive chef position, where he would have free reign to do whatever he wanted. In 2023, he debuted Poltergeist, a separate restaurant within Button Mash that employed local skate kids to grill octopus, set horchata panna cotta, and assemble Thai Caesar salads with smoked anchovies and frisé. In 2024, Diego is affectionately awarded the 101st spot on the LA Times 101 Best Restaurant List. He became a James-Beard semi-finalist for Best Chef California, and then won the Rising Star award by Star Chefs. He filmed spots on YouTube shows, taped an episode of Guy’s Grocery Games, went to GQ parties, and began hanging out with chefs he only used to follow. As we wait on Rich Table’s steps, I’m eager to try its menu of dim-sum-inspired California cuisine with global influences with one of the best chefs in the country who I’m lucky enough to call my friend.

Alas, our escapade at Rich Table is not meant to be. The earliest table they have is at ten, which is eighty minutes from now, and too long to wait. I suggest Picaro, a (very) no-frills Spanish restaurant and classic Mission staple. We snag a table easily in the main, brightly-lit room. Anchovy-stuffed olives and the tortilla go over fine, as do the camarones al ajillo. But as Sincere’s mouth is full of rice that comes with the lamb skewers, he points out that it was made in a factory by Uncle Ben. I enthusiastically encourage Andy to get the fried smelts, but they are stale and stodgy from sitting under a heat lamp for too long. I slump back in my chair and down some sherry as I watch these self-made men whose expectations I undoubtedly disappointed.

I notice Diego silently staring into his water glass, a gamba glistening on his plate untouched. He leans over and presses his lips against my ear in a whisper. He tells me that he doesn’t think Poltergeist is gonna last out the rest of the year. The year is 2024.

2. The Incident

It is 2018.

This Restaurant is not like other restaurants, you think. The Chef is not just highly-acclaimed but world-famous. He’s assembled a team of people who’ve worked at places you’ve only read about – have only dreamed about – and you’ll be working with them closely. You don’t have much experience, yet you beat out who knows how many others to be here. As far as restaurants go, it doesn’t get any better than this.

These are your thoughts as you watch the presentation in front of you, given by a woman with sunken eyes and bad posture. She runs through a history that, unlike some of your fellow cohorts, you already know back to front: Chef dropped out of college to begin his culinary journey. He went to culinary school and spent time in Japan, and upon his return he began working at some of the best restaurants in the City. It is 2004. Feeling stuck in his career and alienated by his own industry, he decided to open a restaurant that would do things differently. It would serve fine-dining-level food but in a casual setting. The menu would be limited and people would sit on backless stools. He would play rock music and play it loudly. And most importantly, he would cook what he wanted instead of what he believed people would want from him.

Fortunately for Chef, his food was groundbreaking. His rebellious approach was a breath of fresh air in a town full of big dining rooms and snooty maître d's. His food was not only good but uniquely his own – his restaurant served dishes you couldn’t get anywhere else. Success didn’t happen right away, but word soon spread, and when it did, it seemed to happen overnight.

It is 2006. The success of Chef’s first restaurant led him to open a second restaurant, which was not a carbon copy but also attempted to change the game. It is 2008. This second restaurant was not as successful at first, so he opened a third one – not because he wanted to, but because he had to, to have a chance of recouping lost costs. Not only was this third restaurant more successful than his first one by a mile, but it really put him on the map. It led to more restaurants, TV appearances, a sneaker deal, and a food magazine that would go on to change food media forever. He had hit some setbacks the past few years, shutting down some restaurants as well as the magazine under mysterious circumstances, but now he was back with more energy than ever. This new restaurant is his boldest project yet.

It is 2018. The woman lowers the microphone as Chef steps out to our applause. He’s no less passionate than I expect, and he expects nothing less from us besides making this the best restaurant in town, something which won’t happen without all of us showing up every day and giving our all. It also won’t happen if we don’t allow ourselves to make mistakes. Others may make those mistakes, I remember thinking, but not me.

Celebrities, their agents, politicians all come; as do chefs, influencers, and Chef’s biggest fans. Every night there’s a line out the door, and some folks wait two, three, or four hours for a table. Sure, it’s stressful – we’re going for Michelin after all. But there is also joy. The food is amazing and I’m learning so much. I crack jokes with my co-workers who, at least when we’re clocked in, might as well be my best of friends. Working here is a once-in-a-lifetime experience, and I crash on my bed every night too tired to shower but proud that I’m doing my part in creating something great, something for the history books (or at least the food magazines). That was of course, before the Incident…

The Incident happens right before service. I accidentally drop an empty water carafe while trying to fill it with ice. I do it while the ice machine is open, and I do it in front of none other than Chef himself. I don’t need to tell you how he reacted. Truth be told, I cannot fault him. Due to the non-zero chance that glass is now in the ice machine, service would now be iceless until the ice machine is cleaned. Who knows how people, many of which may be important food people, would react? A fellow co-worker helps me clean it along with my manager, and, while it isn’t pleasant in the moment, we all laugh about it at the end of the day. I crash, smelly as usual, thinking that is the end of it and that I will never break another glass again.

A few days later, I tune in to hear the first episode of Chef’s new podcast. His podcast promises to offer the truth of the restaurant industry, and chef himself will offer a behind-the-scenes look at the happenings of his own restaurants – the failures and the triumphs. Chef told us once that he's starting this media venture to generate more interest in his restaurants and thus revenue, which will allow him to keep taking care of his employees, i.e. us, in these ever increasingly turbulent times. Imagine my surprise then, as I’m walking to 7-11, to hear him bring up the Incident as a story of something unexpected that can go horribly wrong. He uses it as a hook to draw people in, not to shame me. But even though he doesn’t mention me by name, of course everyone at the Restaurant knows who he’s talking about. Whispers falsely accuse me of shattering the carafe in the ice machine itself. People become curt when before they were courteous. I’m suddenly paired with the toughest of servers who only communicate with fingers and eyes. I break more glass than I ever thought possible. But I also work harder and better than I ever have before. I fold every napkin when a guest gets up from a table. I scrub every toilet and clean up vomit and shit. And, of course, I take care when fetching ice, gently guiding the cubes down each carafe’s bottleneck that is almost too narrow for them to fit into.

“Hey, you’re actually pretty good!” a server says to me once with surprise. I set time to meet with my manager who also tells me that I’m doing great. Maybe everything I was feeling was indeed in my head. Maybe people were loath to work with me not because of the Incident, but because I was indeed so much worse at my job than my snooty-little self I thought I was. Even so, Chef painted me in a negative light. If it didn’t change how people saw me, it certainly changed how I saw myself.

I thought back to the presentation on our first day in light of the podcast. Why did we even need this presentation? The subtext is that it was to motivate us, but Chef could have done that in a million other ways. I saw now the woman’s recitation, the pomp, and through it all the meticulous, clean myth of Chef’s history. Why?

3. The Milk

Via @nytimes

It is 2018. Three hours, two trains, and one car ride later, Ian and I arrive at Blue Hill at Stone Barns in upstate NY. To say that Dan, the chef, is a big deal is an understatement. He popularized cooking with only seasonal ingredients, and the phrase “farm-to-table” was coined in a review of his restaurant. Dan cemented the term “nose-to-tail” cooking, in which no part of any ingredient should be thrown away. He created the honeynut squash and garleek and “ethical foie gras,” raising geese to produce fatty livers naturally by breeding them to crave more food than their peers. His philosophy for why you should go against said grain and mill your own is outlined not only in his episode of Chef’s Table but also in his book The Third Plate, which I read in its entirety before dragging Ian here. The book, as does Dan’s own Instagram, depicts Blue Hill less as a restaurant and more as a Wonka-esque workshop, where magic and whimsy lurk around every corner. There is no menu, only desire. And once you express it, Dan himself will craft a menu especially made for you. This dinner will be very expensive. Might as well get the wine pairing too. My eyes glazed over as the server finished their spiel, there’s nothing they can tell me I don’t already know. I expect nothing less than a transcendent experience.

The first amuse arrives: an array of raw radishes and carrots from the garden, served as is. I pop the small vegetables into my mouth, and Ian asks me if we’re supposed to eat the leaves. Given what I know about Dan, I say “of course” with only the slightest of scoffs. But when I do, I find they’re covered in dirt. I wash it down with a sip of water, assuming that this is just a fluke. But as dinner progresses I notice more things that feel... off. Service is cold and detached, fake smiles frozen on servers’ faces. One of them drops a dish with some ingredient on it I don’t recognize, and when I ask him what it is he rushes away to “ask the chef” – never to return. Our menu does indeed seem unique from many dining around us, but one dish, a scallop burrito, is also served at Blue Hill at Stone Barn’s sister, less-involved, restaurant in Manhattan (also called Blue Hill). Granted, I’m not actually expecting our menu to be completely tailor-made to every guest – the sheer logistics required to pull that off would be impossible. And yet, that is the story Blue Hill chooses to tell us. How would I have felt if I didn’t know better?

More stories soon follow:

a line cook crafts a table-side oat shoot pesto, the oat shoot being part of the oat plant that usually gets thrown away

we’re instructed to enjoy the marrow from a roasted stalk of kale

we’re served squash by itself. It’s been bred for flavor, not size; so sweet that it's roasted without any seasoning or salt. The varietal is still unnamed

we’re told to get up from our table and follow a server into a small, wooden room with three loaves of bread; each loaf represents the Past, Present, and Future, the Future being made from wheat sustainably cultivated by Dan himself

a dish of “glazed carrots and steak” is a play on the classic “steak and glazed carrots”, with the vegetable of course being the star of the show

At the meal’s climax, we’re brought back to meet Dan himself, cooks toiling behind him in an even grid. We exchange brief pleasantries with this ground-breaking visionary while he thanks us for coming and shakes our hands. A server asks if we want our picture taken with him. Of course, we put our arms around him and smile.

“We saw you from across the room.”

As I eat my carrot steak, I remember John Colapinto’s 2012 piece for the New Yorker about Eleven Madison Park, the famed New York eatery which sought to climb up San Pellegrino’s World’s 50 Best Restaurant list and eventually did (in 2016). “The San Pellegrino list rewards restaurants with a strong sense of place, and of theatre,” writes Colapinto, and at the time of his writing, Eleven Madison Park was reinventing itself around a New York theme. Everything from their employees’ uniforms to their table settings were reimagined to be more “New York.” Its menu was rejiggered to “provide more items that are made entirely from indigenous foods, including a course of local cheese and beer, served in a wicker basket meant to evoke picnics in Central Park.” Servers were also expected to “describe the origins of each course, complete with historical dates, names, and facts.” With a focus on storytelling, Eleven Madison Park was able to reach the top spot, to become World’s Best. But a story can hide ulterior motives. Eleven Madison Park’s changes were hotly debated online, “there was surprisingly little outcry over another big change [...] removing the lower-priced prix-fixe options in favor of an obligatory twelve-course tasting menu,” eliminating diner choice while undoubtedly yielding higher margins.

It is 2018. Blue Hill at Stone Barns is No. 12 on the World’s 50 Best List. Rather than champagne or caviar, we are served bread with oat shoots – peasant food imbued with meaning. Worse, in light of an Eater report, Blue Hill allegedly lies about how its food is truly prepared – most egregiously by having guests pick out eggs cooked in a sustainable “compost oven” when in reality cooks placed sous vide eggs inside of it in the nick of time before guests arrive. This is to say nothing of the alleged violent behavior and sexual abuse that also took place at Blue Hill.

And yet. The un-named squash, sweet enough to be served with port, is a revelation. The kale marrow, served alongside a delicate spiral of puff pastry, is something I still long for. TikTokers in 2025 are re-creating it with Brussel sprout stalks. The carrots in our “carrots and steak” dish are glazed in rich beef tallow as sweet as honey, poured from a candle burning on our table. Goose liver richly pairs with chocolate. A slice of bresaola served on Dan’s bread melts away on the tongue like air. But it’s really the milk–fresh from Blue Hill’s own grass-fed cows, ordered on the side with espresso, handed to me as an afterthought–that must be tasted to be believed. It’s floral and nutty and sweet with a flavor of what can only be attributed to what the cow eats on its land, a lactic terroir. Comparing Blue Hill milk to milk from an American grocery store is an exercise in accepting the cruelty of the American agricultural complex. It is the apotheosis of Dan’s mission: that yes, indeed, things can be better.

“Chefs may fool themselves into believing that they’re operating idea factories, that they’re offering intellectual journeys and emotional wallops,” says former NY Times food critic Pete Wells about the World’s 50 Best List, but that they’re doing so in lieu of caring whether people like himself, in his words, “are having a good time.”

I suddenly realize that I have consumed at least two bottles of wine. I return to our table from the toilet, and our servers briskly hand us our coats and show us the door. Upon stepping out into the cold night, I wonder about the consequences of my prior knowledge of Blue Hill. Blue Hill places just as much emphasis on storytelling as it does on its food and hospitality. With self-imposed expectations too good to be true, it’s the only way that Blue Hill can fully deliver.

Not sure what’s going on with the tree/pinecone situation? behind me.

4. The Critic

It is 2018. Three months after we open, the Restaurant’s review by the Critic comes out – right on schedule. While not directly responsible for Chef’s success, the Critic’s influence is undoubtedly unmatched, and his review of the Restaurant is also uncharacteristically critical. Naturally, Chef is furious. He is less upset about his Restaurant being critiqued and more upset about not feeling seen, as if the Critic who he’s grown to love and admire chooses not take his Restaurant at face value and instead jab him just because he can. To the critic’s credit, he reveals that he and Chef have a history, to take his words with a big grain of salt.

Any hope for reconciliation is crushed, however, because not too long after the review comes out, the critic dies. I find out in the middle of service and rush over to my manager who has already heard the news. I half expect service to stop, but it doesn’t. I half expect guests to fall silent, but they just continue eating while snapping pictures of their food. It dawns on me that they do not care about the Critic, even if they have an idea of who he is. They care about Chef. Thus, the podcast: If you speak it, they will come.

But it’s also my duty to pay close attention. While many guests first sit down at their tables squealing with delight, by the end of their meals they’re too engorged to talk, plenty of food in boxes that we hurriedly look for space to pack in the back. For every table that stays long past closing, talking and laughing with a bottle of wine, there are twenty tables that seem like they can’t wait to leave, immediately getting up as soon as they can. Many of the dishes have elaborate descriptions designed to invite curiosity. At first I take my time to describe them, but after I notice guests’ eyes glaze over I begin to shorten them more and more, until I have barely anything to say at all. Most people order more when I do this, and for the longest time I can’t figure out why. But on the day the Critic dies I’m more observant than usual. A two-top in my section has been sitting for hours, holding hands next to a bottle of wine. A six-top wearing merch from their favorite baseball team leaves after 45 min to catch the big game. And there’s the one-top at the counter who just wants to be left the fuck alone. They may be as interested in the Restaurant’s lore as I am, where each ingredient came from, in Chef and Critic’s beef. But these tidbits aren’t useful to their main objective. They’re here, after all, to just have a good time.

***

It is 2025. Much ado has been made about the future of restaurants: if Diego can’t succeed, who can? Tipping has gotten out of control, the cost of goods is too expensive, and with tariffs and immigration laws that may or may not materialize, God only knows what’s going to happen. But if hard numbers are to be believed, we’re spending more on eating out than ever before. The amount of people employed by the restaurant industry has been growing steadily despite a pandemic dip. The myth that 90% of restaurants close in their first year is just a myth, popularized thanks to an American Express commercial.

And yet, a sentiment echoed by chefs in a New York Times article is that things are harder than they’ve ever been before, that “guests have become a lot less kind and understanding.” Meanwhile, on a Reddit thread discussing said New York Times article, many commenters feel that the chefs featured come across as entitled, that they have, as one commenter puts it, “an over-inflated sense of what they give to people.” Whoever is right or wrong is less important than the fact that a gap exists between what chefs think they’re giving and what diners think they’re getting. From both the article and the Reddit thread, you would think that these two groups who are dependent on each other are at war.

Of course, this is just one article and just one Reddit thread about the restaurants we talk about when we talk about “the future of restaurants.” Left unsaid are the restaurants we don’t talk about: the Chinese restaurant down the street, the taco truck around the corner that doesn’t make their own tortillas, the old school red sauce joint that’s just not storied enough, the new school red sauce joint that’s just not dated enough, the hibachi restaurant that closed down due to debt, the sports bar that’s just a tad too expensive, the national chain that’s not nostalgic enough, the fast food franchise that’s just not big enough, the hot chicken joint that’s a knockoff of a knockoff, the mom n’ pop diner that’s nothing special, the little bistro with one great dish, the excellent brasserie that’s a touch too corporate, the bagel joint that just gets the job done. We don’t talk about them because they demand nothing from us besides our patronage and we demand nothing from them besides them being what they are.

It is 2018. One night when it’s supposed to be as clear as crystal, clouds suddenly begin to form up above the Restaurant. Due to what can only be described as an oversight, the Restaurant’s patio was built without a patio cover. Rain comes down on guests while they’re eating, and everyone has to be moved inside. Of course though, all the tables inside are already full. Guests stand on the outskirts of the dining room, the bar scrambling to serve them free drinks. Food that is supposed to drop outside has nowhere to go, and is just piling and piling on top of the pass. The guests who are dry and eating comfortably can’t focus on anything besides the chaos around them. And there is not a thing that any one of us can do about it. Thunder cracks as Chef looks skyward, his shoulders relaxing ever so slightly. Suddenly, the Restaurant’s vibe becomes giddy. Both guests and employees make eye contact and sigh, both of us laughing at the incredulity. Gone is the narrative we relay about this place, to both our guests and each other. The only thing that matters now is to get through the night, and, if only for a moment, we are free.

5. The Future

It is 2025. “Diego’s food often gets labeled as ‘chaos cooking’ or the endlessly cringey ‘troll cooking’ but in my opinion that doesn’t begin to accurately describe what he does at all,” says Danny Palumbo of The Move. “Seeing Diego serve Crunchwrap Supreme lasagna and Hot Pocket agnolotti, to me, isn’t a ‘fuck you’ so much as it’s a gentle, ‘Hey, relax. It’s food.’” Diego’s hey-relax-it’s-food attitude is on full display at our table at Smoke House, one of Burbank’s oldest steakhouses, as our server sets down four different steaks, six sauces, a wedge salad, and three orders of cheesy bread, which apparently is something they’re known for. The cheesy bread is garlicky and covered in cheese powder akin to Cheeto dust. Also like a Cheeto, it is indeed addictive.

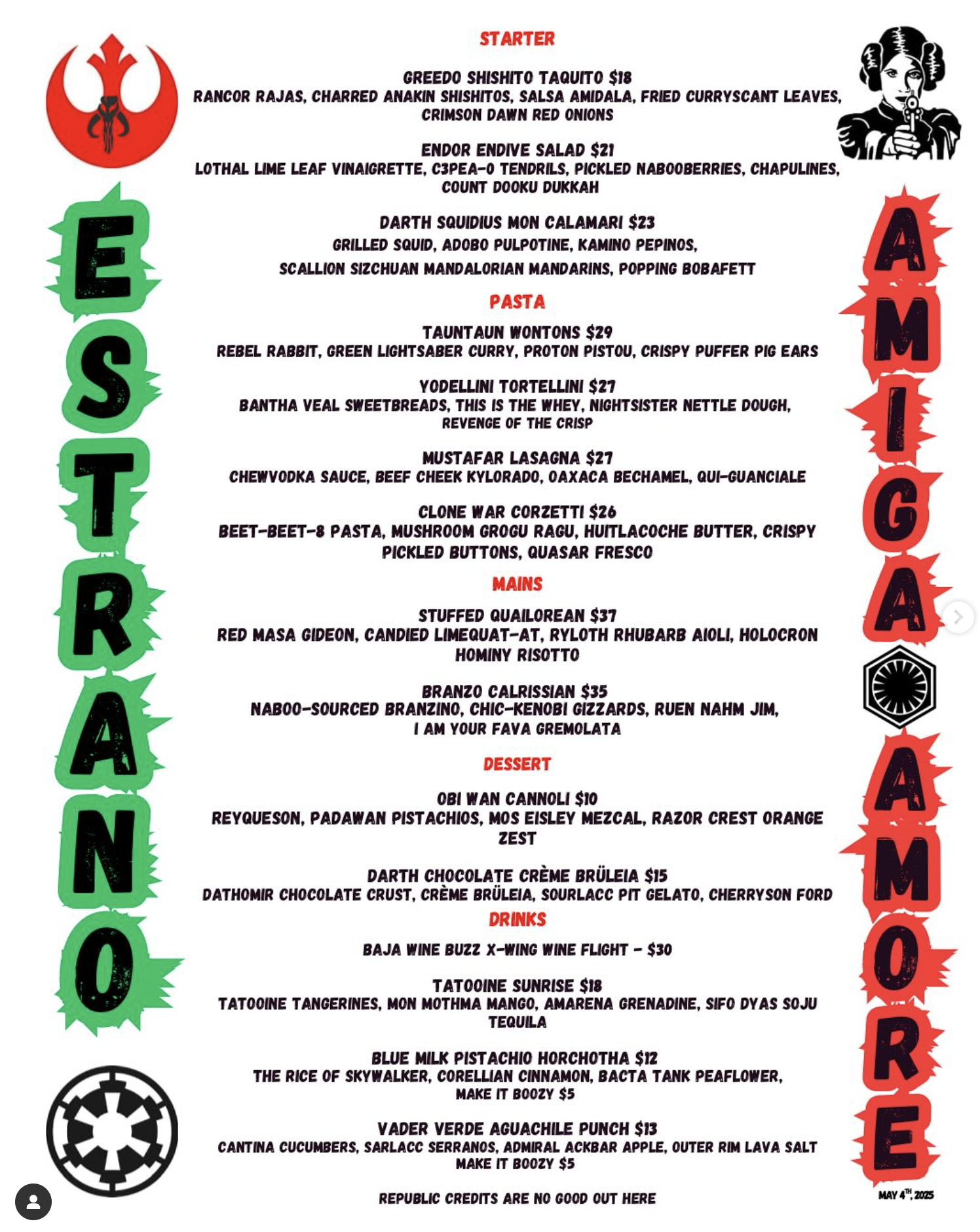

If you think losing Poltergeist set Diego back, you’d be wrong. Not a full 24-hours after he made the announcement, he received another executive chef offer at another prestigious locale. He makes more money than he’s ever had before and is no less regarded, in fact more so. He frequently attends celebrity chef events, sometimes cooking alongside them. He wears designer jeans and his thick hair in a ponytail. He also still pops up as Estrano, most recently for Star Wars day, aka May the Fourth. He made green Yodalini and Obi-Wan Cannoli. And he charged Galaxy’s Edge prices – perhaps what he always needed to make things really work. Maybe running an arcade bar and a trendy restaurant from the same space at the same time is in fact more difficult than one might imagine. Maybe a mostly-vegan food court inside an Ikea next to the Tenderloin isn’t exactly the best idea. Maybe a restaurant that manufactures exclusivity is, in fact, not meant to last, even if it is sure fun to read about.

“It belongs in a museum.”

It is 2025. Andy has a restaurant deal fall through but becomes more popular than ever. Sincere receives a nod from the SF Chronicle in the form of an explanation for why he didn’t make their Top 100 Restaurants list – they only included actual restaurants.

It is 2025. Dan has turned Blue Hill in Manhattan into a dinner party experience. A fire breaks out at Blue Hill at Stone Barns, but thankfully no one is hurt and minimal damage occurs. Guests are now given a tour of the farm before diving into a six-and-a-half hour meal.

It is 2025. Chef has a Netflix show. He has a brand. It’s leaned into consumer packaged goods.

It is 2025. In an Eater LA article, the restaurant Ki is profiled. Located in the basement of a Little Tokyo office building, it’s “perhaps the most exciting new modern Korean restaurant in Los Angeles.” The multi-course tasting menu starts at $285 per person and “weaves through a deeply personal narrative.” We see each course in beautifully composed photographs and read detailed descriptions about the lobster with doenjang and raspberry, the cod milt with bugak and red pepper, the horse mackerel with aged kimchi and perilla. The article paints such a clear picture of what to expect: another transcendent experience.

But it is 2025 and I am not at Ki, but rather at an establishment full of white tablecloths and bright red booths. I ingest a piece of “Tournedo of Beef.” The meat is tough and under-seasoned. The breaded tomato it comes with is strange. But my martini comes with a sidecar, and our conversation is heated and fun. We certainly don’t expect to have the meal of our lives here. But for whatever reason, we do expect to come back.

I shove more cheesy bread into my mouth.