What We Talk About When We Talk About “What We Talk About When We Talk About Corndog Restaurants”

That ‘tis the question…

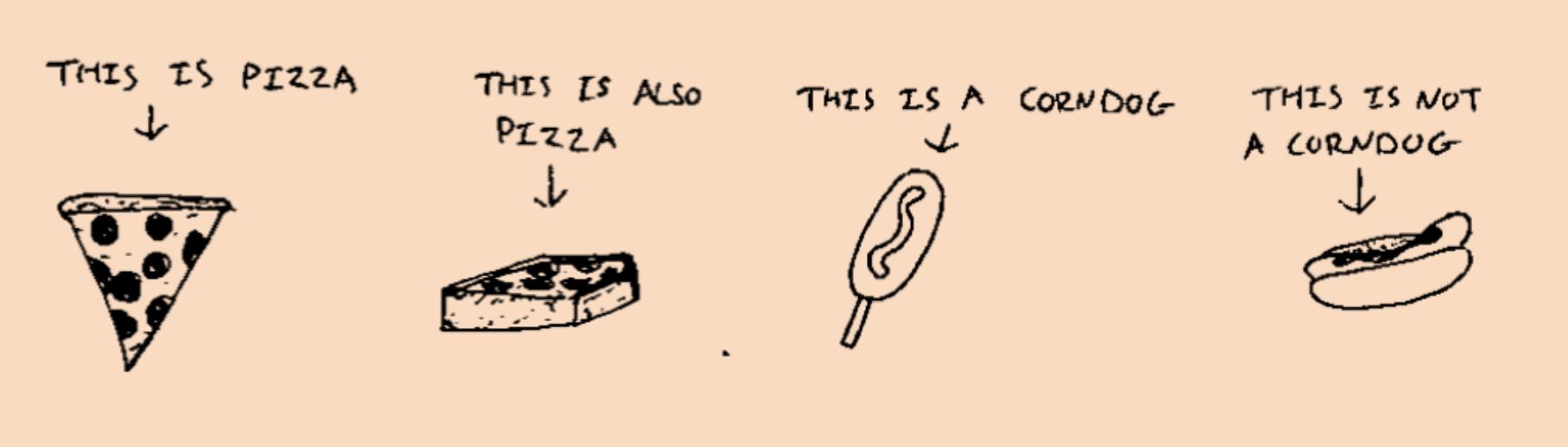

Before we can talk about what we talk about when we talk about “what we talk about when we talk about corndog restaurants,” it is necessary to identify the concept of a “corndog.”

Insert Magritte joke here.

A corndog, of course, is a hot dog skewered on a wooden stick, dipped in cornmeal batter, and deep fried until both the batter is cooked and the hot dog is heated through. Like the hot dog itself, a corndog is a beloved yet cheap fast and processed food often made with leftover pork product (or turkey product, in the case of Hot Dog on a Stick); but even more so than other fast foods like pizza, cheeseburgers, or even hot dogs themselves, a corndog must always consist of the same basic components of dog, batter, stick; comparatively speaking, the floor is high and the ceiling is low (🤏) on not just how “good” or how “bad” a corndog can be, but what it can actually be.

It’s math.

An elevated corn dog, made with Iberico pork and truffle batter (let’s say), is still a piece of deep fried pork meat at the end of the day; you may be vegetarian or just not like that sort of thing, but there is no question that it will have its audience. Now we know what a corndog is, we can talk about the Corndog Principle, Problem, and Paradox respectively.

The Corndog Principle

Obviously the corndog is a metaphor here: a corndog in the restaurant sense is a restaurant that is not just well-known but, for one reason or another, can’t be anything other than what it is. The House of Prime Rib is a perfect example of a corndog restaurant: it’s been around for almost a hundred years, its interior has remained the same for decades, and they have always only served, as its name implies, prime rib. Would you go there and be mad that they don’t have filet mignon? That would be illogical, they only serve prime rib. Would you comment upon leaving that it was good but that it would be better if they also served lobster or shrimp? You could, but that would speak more about your preferences than point out a flaw in the restaurant itself; they only serve prime rib... that’s their thing. Would you be right to compare it to Musso’s or Lawry’s, two other corndog restaurants that have also been around forever, have a similar aesthetic, and also serve prime rib? You could. You may even prefer Musso’s prime rib to the House of Prime Rib’s prime rib. But again, that does not make the House of Prime Rib a lesser restaurant because of it; there are other aspects to the House of Prime Rib (ambiance, service, etc.) that Musso’s and Lawry’s do not have. If you put a frozen corndog and freshly-battered corndog side by side, the freshly-battered corndog would be the clear winner when taking taste into account alone. But the frozen corndog wins for convenience by a mile. The freshly-battered corndog and the frozen corndog are both successful for their intended purpose; therefore, while you could have a personal preference for either The House of Prime Rib or Musso’s or Lawry’s, they ultimately all succeed at being their own thing. Hence…

The Corndog Principle: every corndog is equal in value to any other corndog.

This is also math.

The Corndog Problem

In her piece about Disneyland food for the New York Times, food critic Tejal Rao, who spent her childhood eating ice cream at Disneyland Paris, attempts to review a corndog:

“I’d tasted so many snacks by then, I was almost non-functioning as a critic, unable to process. The corndog was fine, but in the chaos of the park during the surge of spring break, after walking about 10,000 steps [...] the corndog was also more than fine […] it was consolation, fortification and even joy. For a minute or two, the corndog at Disneyland was everything.”

In lieu of a straightforward review of Disneyland food, Rao gives us a thinkpiece about the impossibility of being a completely objective reviewer, of reviewing an object removed from not only context and setting but emotion as well. One may agree with Rao after reading her piece; “the corndog is fine and more than fine” is an apt description of what to expect from a corndog at Disneyland, a corporate theme park at the end of the day but one in which (hopefully) you’re having a good time.

Then there’s chief LA Times food critic Bill Addison’s peculiar review of Napa Rose, a fine dining restaurant at Disney’s California Adventure:

“I ask myself what I hope [kids] lucky enough to be eating at Napa Rose might remember. Certainly not some vague theme of ‘Wine Country cooking.’ What does that even mean? Tacos are as meaningful as tasting menus in the culinary landscapes of Napa and Sonoma. I’d want the flavors on their plates to tell them a story of California’s cultural pluralities.”

Mind you, Disney has restaurants in the Michelin guide. But Napa Rose, like every restaurant at every Disney park, including every multi-cultural foray at Epcot and its International Food and Wine Festival (also returning to California Adventure), is a corndog restaurant: their identity is pre-dictated by what corporate allows them to be. This all goes to illustrate how difficult the job of a restaurant critic is. It is one thing to give a bad review to a restaurant that serves you an undercooked piece of meat, but it is another thing to articulate why a piece of meat does not live up to expectations at a corndog restaurant, which, as we’ve established, cannot be better or worse than it already is. We can’t fault Rao or Addison for bringing their own sensibilities to Disneyland – in fact, we expect them to. What we can do is ask why two of the most respected food critics in the country are reviewing Disneyland food, aka corndogs, to begin with? What novel take can one possibly have upon reviewing a Chuck-E-Cheese pizza?

“It takes well to ranch,” the review might read. “but it also gave me diarrhea.”

“What if I have a strong stomach and don’t like ranch?”

“If you don’t like ranch, you might not like this pizza.”

“Does that mean the pizza was bad?”

“The pizza was bad, but it was also less than bad,” the reviewer remarks as they watch the child they love wolf it down.

The Corndog Problem: how does one write about a corndog in a fresh light? What information can be given that we don’t already know?

“Am I a dumpling?”

The Corndog Paradox

Over the past few years, major food outlets have reviewed various corndogs, i.e. successful restaurants that have no reason to change: the French Laundry, Spago, Din Tai Fung, Carbone, Alinea, Chez Panisse. This trend perhaps started with Pete Wells infamous “bong water” review of Per Se, knocking it down from four stars to two, when it wasn’t yet clear what its identity would be. With the pressure of the corndog problem asking “why would you re-review these old-ass restaurants,” they’ve come up with the clever tactic of investigating if they are still “worth it,” if they are as good as people say they are, or if they are still relevant to the cutting edge of the food scene. But remember, there is a limit to how good and also how bad a corndog can be. Naturally, these reviews all struggle to answer the question:

Patricia Esparza on Spago: “In a city where the most interesting cooking often happens in sweltering food trucks, strip mall kitchens and backyard pop-ups, Spago is no longer innovating. [...] For a certain segment of Angelenos, no amount of airy discussion will change the fact that it still feels like home.”

Melissa Clark on the French Laundry: “As fine dining, it was tediously, if inconsistently, fine.”

Melissa Clark on Din Tai Fung: “From everything I know about Din Tai Fung, it’s a safe bet that someone, in some location, is enjoying a perfect xiao long bao. If you want to try your luck at the New York branch, there’s a small chance it could be you.”

Priya Krishna on Carbone: “Carbone is like a movie franchise that keeps getting rebooted, even though the original hasn’t aged well and the sequels aren’t stellar, either. But like those films, you don’t go to Carbone expecting a cutting-edge experience.”

Ligaya Mishan on Alinea: “The first time, I take a nibble and [the edible balloon] shrivels and congeals, chemically sweet on my tongue and tough as rubber. Nevertheless, the second time, the balloon’s arrival is magic again, as if I’d never seen it before. Everyone shrieks with joy.”

Bill Addison on Chez Panisse: “I’d settled into my seat anticipating transcendent, almost otherworldly intensity from every bite. Instead I endured mere perfection.”

Soleil Ho on Chez Panisse: “Overall, the experience of dining at Chez Panisse is so comfortable, its culinary philosophy absent of any sense of urgency.”

“When revolutionary movements fizzle out,” Ho writes in their review of Chez Panisse, “the memory of them can become intoxicating, fixing us into place when we’ve considered the movement a job well done.” And at one point, all of these restaurants were considered “revolutionary”; Chez Panisse was part of the garlic revolution, it revolutionized farm-to-table cooking in America, it helped invent and define California cuisine. There can be a palpable anger when a restaurant like Chez Panisse, which cooks French food and owns its own property, feels like it’s not trying so hard; that it still continues to get recognition at the expense of other restaurants that are equally deserving, like Rintaro, an exciting Japanese restaurant helmed by a Chez Panisse alum who shares a lot of Chez Panisse’s clientele. From a queer perspective, it is valid to want more out of a restaurant with a revolutionary label. To continue wanting more.

And yet, when investigating the relevancy of once-greats, the general consensus of most of these reviews, which are all peppered with both good and bad experiences, is that “there are better restaurants, but those who go to them will like them no matter what,” leaving a reader still with no more compelling reasons to spend or not spend their money than they had before, still succumbing to the Corndog Problem.

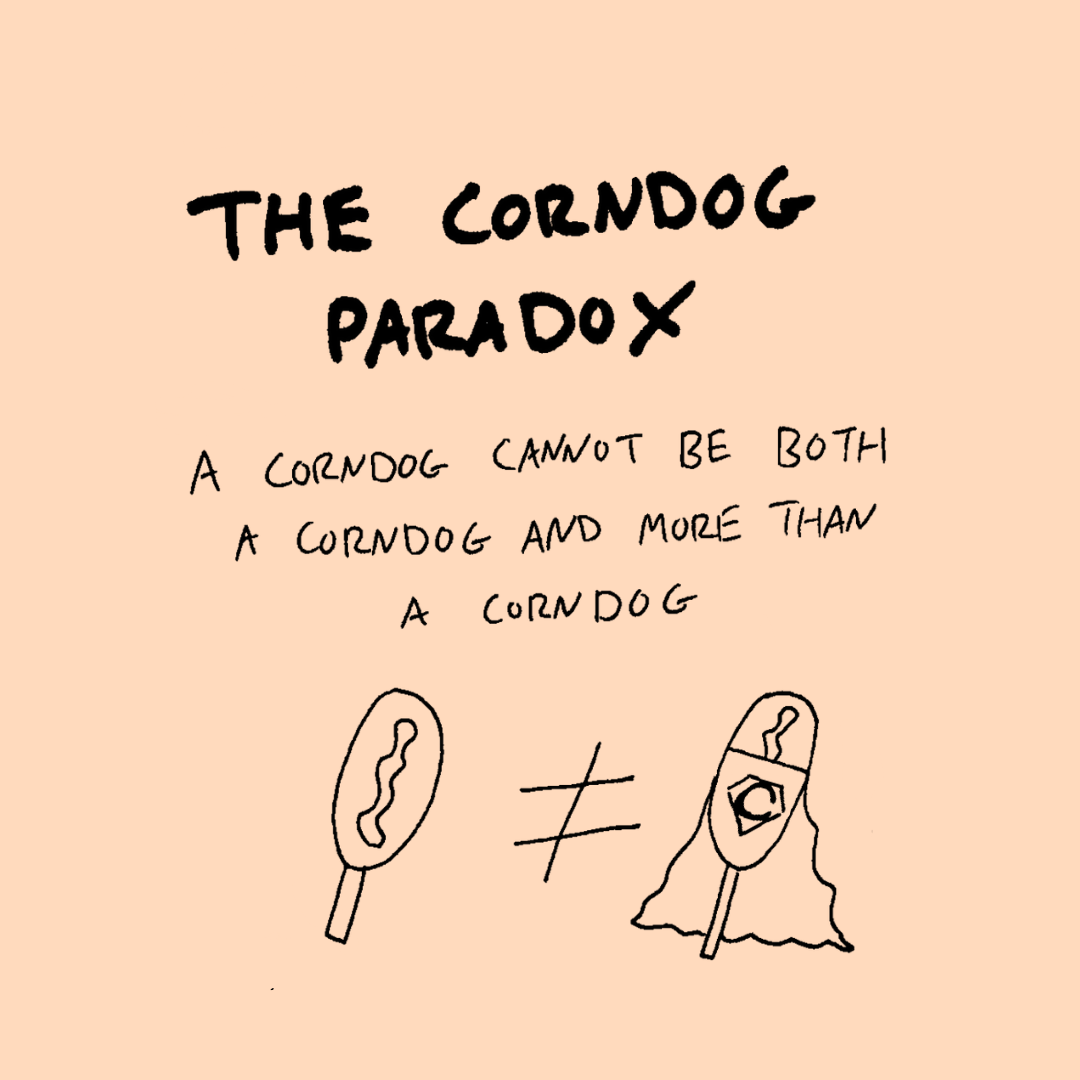

The faulty logic at play shows itself once we substitute our corndog metaphor: if one critiques a corndog for not being as relevant as it once was, or for being more relevant than ever, one denies the corndog’s own fixed identity. One wants the corndog to be more than a corndog, but at the end of the day it is still just a corndog. Thus…

The Corndog Paradox: a corndog cannot be both a corndog and also expected to be more than a corndog.

Directed by James Gunn.

The Corndog Solution

It is not a bad thing to be a corndog restaurant: it means you’re successful, beloved, and an established part of your community. But most corndog restaurants don’t start out as corndog restaurants, they become that way over time through success and reputation. Spago is so old that Jonathan Gold grappled with the same question of its relevancy as Tejal Rao just did after it was recently redesigned.

“The first responsibility of any great restaurant,” Gold writes, “is to keep you in the bubble, the soft-serve cocoon of illusion where you forget the world exists for anything but your pleasure.” He goes on to describe the “important art” on the walls, its past history as a welcome, less-fussy answer to chef Wolfgang Puck’s Ma Maison, and its current dishes inspired by 50-Best-class restaurants in Spain. On talking about its raw fish offerings, which, compared to other sushi restaurants in town, “the match probably goes to the specialists, but it is a testament to the Spago team that one even wonders about the question. [...] You are still at Spago. All is right with the world.” In contrast, Rao writes, “Spago has somehow regressed into the overworked presentations and muted flavors it once rebelled against.” Yet, she also writes: “this might suggest it’s no fun to go to Spago, but the weird thing is, it can be. [...] Some servers are in fact so good at what they do, you could forget that most of the very expensive meal is not great and just enjoy the feeling in the room, depending which one you’re in.” Is Spago the same restaurant that it was thirteen years ago? It’s reasonable to assume that probably not, and that Rao is in deliberate conversation with Gold all these years later. But if you compare these reviews side by side, both come to the conclusion that there’s something unique about it, that it treats its regulars well, that it's still a good time even though there’s technically better food elsewhere, and that it still manages to be very much part of the conversation. So which review should be taken more to heart: Gold’s rave or Rao’s pan? Are not both critiques commenting on Spago’s meat, stick, and batter?

Perhaps that depends on what you’re expecting. We don’t expect corporate or mom-and-pop corndogs to be amazing restaurants, because they never were amazing restaurants, but “the reason why you might save up for these Michelin-starred meals is precisely for that Peter Pan ‘Do you believe?’ moment,” writes Ho in their French Laundry review. “You want to enter a state of extreme sincerity: to clap your hands and convince yourself that you had something to do with Tinker Bell’s resurrection.” Is that fair? Corndogs like Spago or The French Laundry or Chez Panisse became corndogs for changing food culture, so we still expect them to be some of the best restaurants, long after the best ideas they ever had have been adopted and proliferated and reheated and commercialized in the 40 years since they opened. In Bill Addison’s review of Spago in 2019,

“[...] in the quiet moments between courses I think about other special-occasion splurges around town where I’d rather find myself that night. And then I look over and notice the contented couple next to us. They chat familiarly with the staff. They’re both having the schnitzel. Spago will always have its audience. And while I will forever think fondly of that strawberry kardinal schnitte, I realize that I will never be one of its regulars. That’s fine. The beauty of Los Angeles is that, nowadays, no single culinary icon feels like the center of our dining universe.”

We know restaurants like Spago are not “relevant.” They are not because seasons change and time passes by. The talent amongst Season 21 of Project Runway is unquestionably better than Season 4 of Project Runway, every student must surpass its master, but also Christian Siriano (the winner of Season 4) is the most famous contestant to come out of Project Runway in its entirety; once an upstart who didn’t listen to his mentors, he’s now replaced Tim Gunn as the curmudgeonly tut-tutting old hat who no one listens to.

A corndog, while delicious as an adult, will not change your life like it did at Disneyland as a kid. But that also doesn’t mean it’s mediocre. It might, in fact, be what you keep coming back to. What we talk about when we talk about corndog restaurants is that precise quality of familiarity, so desirable yet so hard to come by. When we talk about “what we talk about when we talk about corndog restaurants,” we talk about if it’s fair for that familiarity to hold weight when reviewing a given corndog restaurant. What we talk about when we talk about “what we talk about when we talk about corndog restaurants,” is not only the restaurant’s legacy, but also that it doesn’t matter what we think, because our opinions are unlikely to matter anyway. “It’s the risk when a real, working restaurant ascends into cultural lore,” writes Addison in his review of Chez Panisse. “It can be the most glorious food on Earth, but it will still always simply be food.” What if that is very much OK?

Maybe that’s something to be celebrated. The corndog is fine and also more than fine.

THE END

We love a diva.